Pandemic mitigation measures have mental health side effects

I’ve struggled with anxiety much of my life. In therapy I learned not to put my life on hold to avoid risks… and then a pandemic came along and I’ve been forced, along with everyone else, to do just that. I’ve been forced into the kind of safety behaviours I’ve previously worked hard to stop. I get why, of course, but it has been problematic for me.

I recently tested out how it felt to not wear a mask in a supermarket. It made me feel nervous about breathing, as if the air inside the shop is toxic. That’s what I’ve internalised over nearly two years.

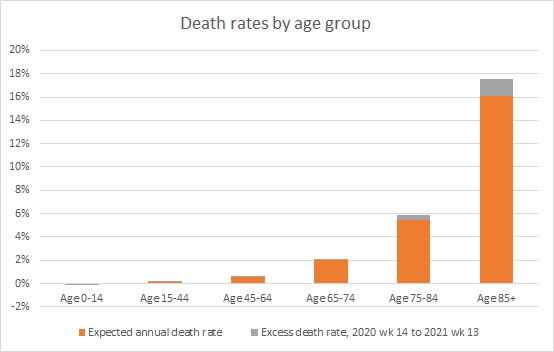

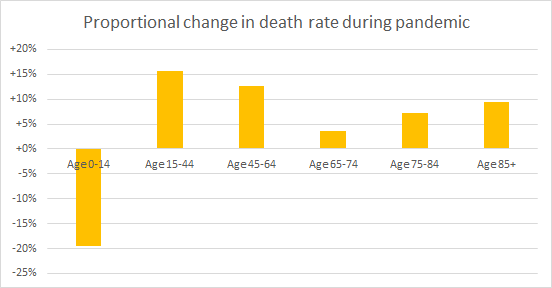

It’s not just me. From the beginning we all had to participate in measures to inhibit the spread, and this seems to have conditioned most people to believe that they are protecting themselves from danger, despite the huge risk gradient with old age. It didn’t help that we had to ditch the narrative of flattening the curve with its unpalatable implication of accepting some severe disease and death. The aim was to save lives and protect the NHS, but you were more likely to see shops and restaurants and schools and so on claiming they are “keeping everyone safe” with hand sanitiser and screens and distancing. This continues long after mass vaccination! As well as both expressing and creating excessive anxiety, I think it also fuels conspiracy theories that may seem to make more sense to people who are immune to excessive anxiety and can see what utter bullshit “keeping everyone safe” is.

The slow pace of return to normal frustrates me so much. I desperately want a day to come when I can go into a shop or restaurant and never once have to think about that virus. And if not now, after 3 vaccinations, then when?? What more is going to change?

It’s been very strange to me that people who aren’t generally anxious types express feeling “not ready” for mask mandates to go or mandatory self-isolation to end, or they uncritically echo sentiments about “staying safe”. But I guess for most people it’s not a huge problem becoming used to safetyisms. It’s only for someone recovering from anxiety that there is always that awareness of how it becomes a trap you can’t get out of. I’m not willing to accept that this is how it is now, for ever.

The rationality of bug-chasing – or at least, we need to move on from “avoid it at all costs”

Rachel Zoffness in this video discusses “bug-chasers” (people who sought HIV infection). I got it immediately. The relief of getting something you’re terribly anxious about, out of the way, is sometimes strangely attractive. I felt like that when I got my first AstraZeneca shot. It wasn’t that I’d seen enough data yet to convince me the VITT risk was tolerably low in my age-sex group. It was more that I was tying myself in awful knots over the issue and I just needed it to be over.

The messages of “you don’t want omicron, don’t seek it out” have massively stressed me out, against the backdrop of the growing consensus that it’s going to be endemic and we’re all going to get it multiple times (which some have been saying for a long time). It’s kind of like telling a pregnant woman, you don’t want to give birth because it might not go smoothly. Try to avoid it.

Let’s just be clear, if you believe (1) it’s inevitable you’ll be exposed at some point before too long (which is the implication of “endemic”), and (2) the danger (or even just unpleasantness) in that first exposure will only increase the longer it takes for it to happen after being vaccinated/boosted… then you will rationally conclude it’s better to have the exposure now. It’s never going to be any safer.

I read recently that if you’re exposed to a virus and don’t get infected because you have antibodies, your immunity still gets a boost from that exposure. That would be why little kids have constant runny noses in the first year of nursery, and then barely get a sniffle. I’ve heard often it’s the same for staff working in nurseries – they get ill a lot at the start, then are hardly ever ill after that despite swimming in a constant soup of germs. Their immunity is continually boosted without the need for symptomatic infections.

We were ill constantly for months when Eilidh first started nursery. I expected this autumn to be the same, as everyone was saying lockdowns had weakened herd immunity. But it wasn’t. I started to realise we have come through the other side and yet I hadn’t moved on from crisis mode where I can’t plan anything because we might be ill and I count down the weeks to the next nursery holiday hoping we can get through them relatively unscathed.

Which is basically what the public health leadership have been doing in this omicron wave.

The only way out is through. We need leadership that recognises that and instils courage, and advises on how to prepare for the journey. Instead all we get is fear-stoking, safetyism, and confusing shit. All of which is either bad for your mental health, or else it fuels suspicion about the vaccines.

I don’t feel safe

Not so much because of the virus, now, but because of the shocking realisation over the last year and a half that nobody in charge of anything knows what the fuck they are doing. It’s coming out as anger.

- There has never been strong evidence for cloth masks and nobody seems to have tried to generate any quality evidence over this pandemic. Same could be said for several other measures.

- Two metre distancing in long meetings, perspex screens – has no-one heard that aerosol transmission is a thing?

- Sanitiser, deep cleaning, disinfection of “touchpoints”, advice not to share pens(!) – have they not heard that surface transmission isn’t much of a thing?

- Setting dates far in advance for dropping of mandates – who decides that, and how?! Likewise coming up with stepwise and pseuo-quantitative frameworks for lifting measures, as if there could possibly be any evidence to lift measures that have no evidence in the first place.

- What is the sense in mandating vaccines for an endemic virus, that can’t stop transmission or eradicate the virus (unless you boost everyone every 3 months), and therefore beyond the first few months only really benefit the recipient. All the vaccines do is ensure some of your first few exposures are “safe”, because they’re to the vaccine and not the virus (although it must also be acknowledged there are some severe and even fatal vaccine side-effects…) so that when you later meet the virus you’ll have a head start. It won’t be long until there’ll be no difference between being vaccinated or unvaccinated: those who didn’t get the vaccine will get their first exposures to the virus instead and ultimately be in the same place. If you want to mandate vaccines, mandate them for over-65s – at least that would have a noticeable impact on hospital admissions and deaths. Not for all these other groups that are being coerced (around the world)

- Inaccurate memes posted on social media by NHS organisations, minimising dangers of vaccination and making false comparisons. Doesn’t it make you go slightly crazy to realise they can’t be trusted to provide balanced and accurate information?

What will endemicity look like?

Covid is not, yet, like anything we’ve lived with before. It feels like it could easily ruin a holiday even if you were allowed to travel with it, because it’s nasty and very catchy and it’s still surging unpredictably all over the place. No-one ever used to hesitate to book a holiday because they might get ill while on it. Will we ever get back to that? If we were to just treat it like any other illness and go back to normal, how often would we all get it? How often would we have 1 in 20 people infected at once?

I suppose the dynamic of an endemic virus depends on how transmissible it is, measures taken to inhibit spread, how long immunity lasts, and then if immunity can be topped up asymptomatically through exposure (I think this is probably the case).

They talk about the very high R0 of covid now, that it’s nearly as infectious as measles. I get the impression that’s unusual, i.e. other colds are not like that. So what effect will that have in the endemic state?

For a start, I don’t really understand “endemic state” at all. Given the huge number of viruses causing cold symptoms, we must get infected with each individual one very infrequently. Yet it doesn’t seem to take long for young children to build up a good level of immunity to common viruses and stop getting ill constantly – maybe a year. Can they have had all the hundreds of viruses in a year? Surely not.

Adults notice an increase in our rate of infection when our child starts nursery or we start working with young children. Presumably because life before that – including going on buses, working in an office, going in shops, restaurants etc – did not provide the same level of exposure. But our immunity adjusts, similar to that of a young child. It seems like whatever our regular level of exposure to viruses, we eventually somehow settle into a state where we get ill maybe 2-4 times a year!

The difference with covid might be, if it’s really so much more transmissible, then close contact isn’t needed for exposure. Maybe we will all have regular exposure just from walking past people in shops or sitting next to them on buses. What difference will that make to the dynamic? Maybe not much in the end. Maybe we will just settle into the same sort of equilibrium we all have with the other viruses whatever our exposure level to them… however that works.

If anyone knowledgeable happens to read this, please do let me know.